Station Eleven and the Corruption of My Dreams

The best way to cope with a real life pandemic is to read a novel about an even worse pandemic that gives you nightmares (major spoilers ahead)

In Station Eleven, 99% of humanity dies due to a swine flu pandemic that kills people within 24 hours of infection and civilization as we know it is lost—cars without fuel, cell phones without service, laptops without wifi, light bulbs without electricity, debit cards without bank accounts. There are many dead bodies and much savagery. (Like The Road; but unlike The Road, there is a (very hot) sun and nature thrives in the post-apocalyptic world.)

I had heard a couple professors talking about whether or not they should go through with teaching the book when COVID-19 hit in mid-March. I made a mental note of the plot of the book, being familiar with its title but not knowing what it was about. Seven months later I have my chance to read it like a student: a Shakespeare class I am supporting this quarter is reading the book and I am invited to engage with the class on the archival themes in the book—the theme of what is valued enough to be kept. In this fictitious world, written texts are foraged from houses of dead people and are prized highly. The printed material mentioned in this post-apocalyptic world is a mix of high and low culture:

TV Guide

Tabloid/gossip magazines

Poetry (always the first to be taken from a ransacked home)

Shakespeare (but an insufficient representation of the theatre arts, one character feels)

Homemade newspapers by a French copywriter turned librarian turned oral historian (in any type of society or community, a news source written by members always emerges: concentration camps, prisons, universities)

The super rare comic, Dr. Eleven

These high-value artifacts of written culture are singular in their scarcity, placing an emphasis on what remains in Year 20 more than what is valued; as heavy as the significance of a traveling symphony performing Shakespeare is, Kirsten’s tattoos signal something more:

Diallo: No, no, the other one. The two black knives on your right wrist.

Raymonde: You know what tattoos like this mean.

Diallo: But perhaps you could just tell me—

Raymonde: I won’t talk about it, François, and you know better than to ask.

Marks on the body numbering homicides become a prototypical alphabet; they can always be carried and can always communicate a message of self-defense. Unlike the books, comics, and newspapers. But Kirsten always looks for more:

They left with a suitcase each, towels and clothing and a stack of magazines that Kirsten wanted to go through later, an unopened box of salt from the kitchen and various other items that they thought they might use, but first Kirsten lingered for a few minutes in the living room, scanning the bookshelves while August searched for TV Guide or poetry.

“You looking for something in particular?” he asked after he’d given up the search. She could see he was thinking of taking the remote. He’d been holding it and idly pressing all the buttons.

“Dr. Eleven, obviously. But I’d settle for Dear V.”

The thing that represents the power of the history of print culture is the very device that strings the story together. The actor Arthur Leander, who Kirsten had worked with as a child actor and who had a famous enough life that traces of him could be found in the printed record, animates Kirsten’s connection to what material culture remains after the collapse. Dear V. was a collection of letters Arthur had written to a childhood friend that was published later against his will, causing a scandal. The purpose of the magazines Kirsten takes from the home in the scene above is to perhaps locate a trace of Arthur. Dr. Eleven was given to Kirsten by Arthur, and written and illustrated by his first wife Miranda, who we get to know quite well in the book.

The print culture that remains in Station Eleven represents memory, the past, identity, and any one person’s connotation to the object: the only remaining information of Arthur Leander is in print rather than another medium, and for Kirsten, Arthur Leander is a lifeline to her own history. By searching for traces of him, she stabilizes her own lost memories from before the Georgia Flu hit and perpetuates the mythology of the old world, simultaneously giving hope to the possibility of recreating the best things that were lost in the collapse.

So too do archivists and librarians in the year 2020 collect specimens of material culture that best represent memory and identity as it relates to their own identities and the identities of the communities they serve (if they’re doing it right), but not nearly in such a dire environment as in Station Eleven.

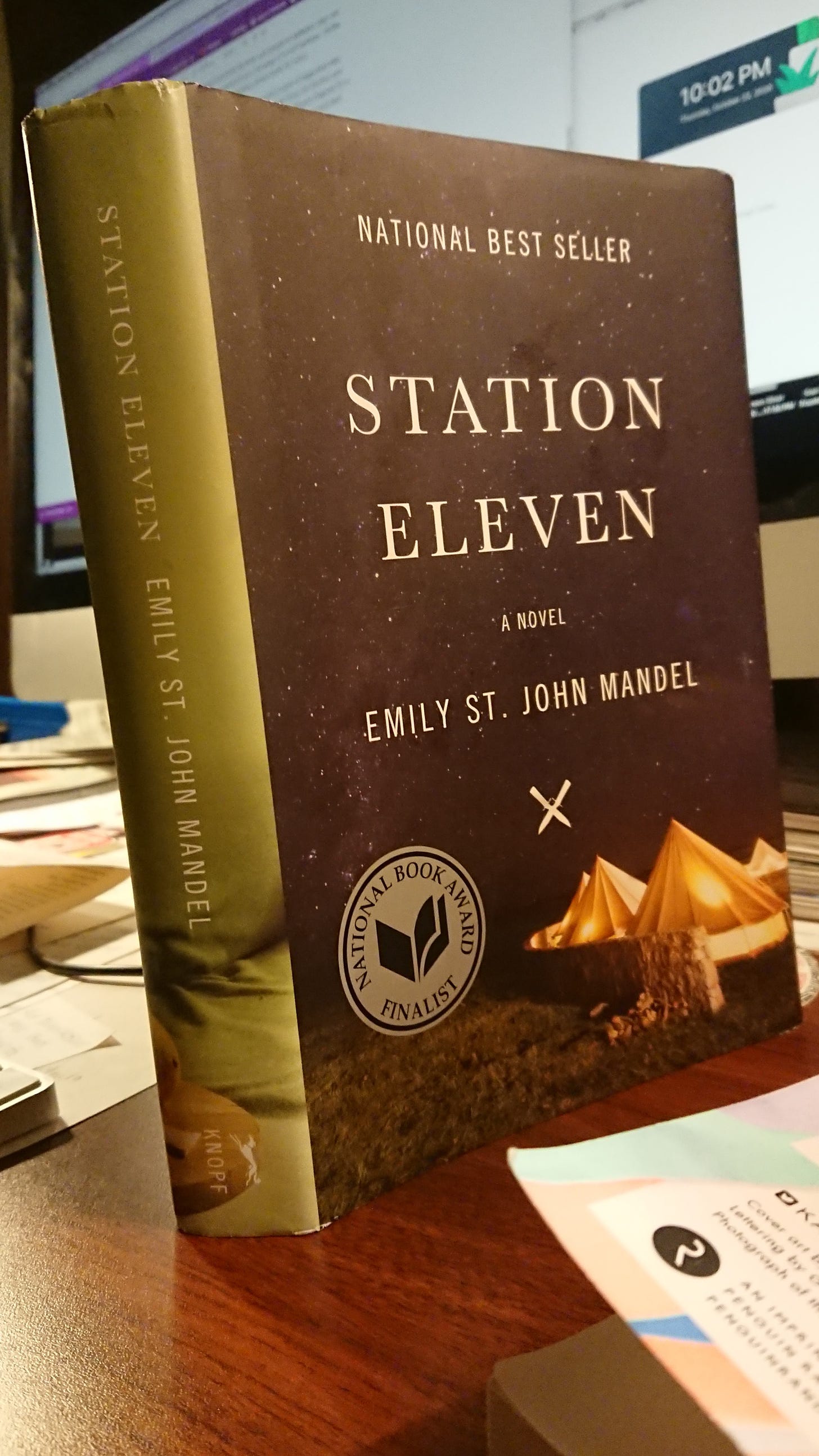

I got this hardcover used at Green Apple Books for $12. (There was a kerfuffle related to the book being on hold and the employees did not seem happy that day.) It is the twenty-sixth printing, which took place in January, 2019 even though the book was originally published in 2014, and it credits the book designer, Abby Weintraub, who used two stock photos for the front and the back of the jacket, respectively. It is set in Janson, which the matter at the end of the book clarifies wasn’t designed by Janson at all, but by Nicholas Kis.