Several years ago I sustained a shock to the system that encompassed most habits of my life: I quit smoking cigarettes, went sober (to help with the not smoking), and went through a breakup all about at exactly the same time (do not recommend). To cope with losing my usual social outlets that revolved around drinking, naturally I joined a “Great Books” discussion group at the Anza Branch of the San Francisco Public Library. The group would meet one Saturday afternoon per month, and would alternate between discussing a short story or a piece of classic philosophic writing. The discussion ran on the shared inquiry method, which relies on textual evidence for discussion.

There were some tense moments in discussion, especially when a newcomer would violate the rules, but the diversity of the group produced unique insights. Most attendees were over 50 but some were younger; for many, English was not their first language; they didn’t have advanced degrees in literature or come from monied backgrounds; most definitely this wasn’t a group of upper middle class white ladies getting together with an excuse to drink wine. Most amusingly to me, I got a front row seat to the conflicts that arose within this motley crew of San Franciscans: at most meetings the moderator/organizer would briefly lose control and whoop on someone for not following the rules or some other transgression. The conflict would sizzle for a tense few moments, and eventually the moderator would apologize.

After some years, I was initiated into a heavier, special session of the discussion group, where the members occasionally selected an entire book to read and discuss. Following the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, the group chose Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and I agreed to get in on the action—I always felt I should have read since it encompassed so many of my interests (the Beat Generation, the Hippies, psychedelics, road trips, etc.), but had never gotten around to it.

Plus, Tom Wolfe was an old man by the time I became aware of him in High School—pictures of Wolfe in a crisp white three-piece suite to match his white hair were everywhere the summer I was 15—A Man in Full was apparently a big deal and all the adults seemed to be in on something I wasn’t privy to. This was my touchstone for Wolfe, not his journalistic period in the 1960s tagging along with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters (in fact, I never got around to reading One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, either).

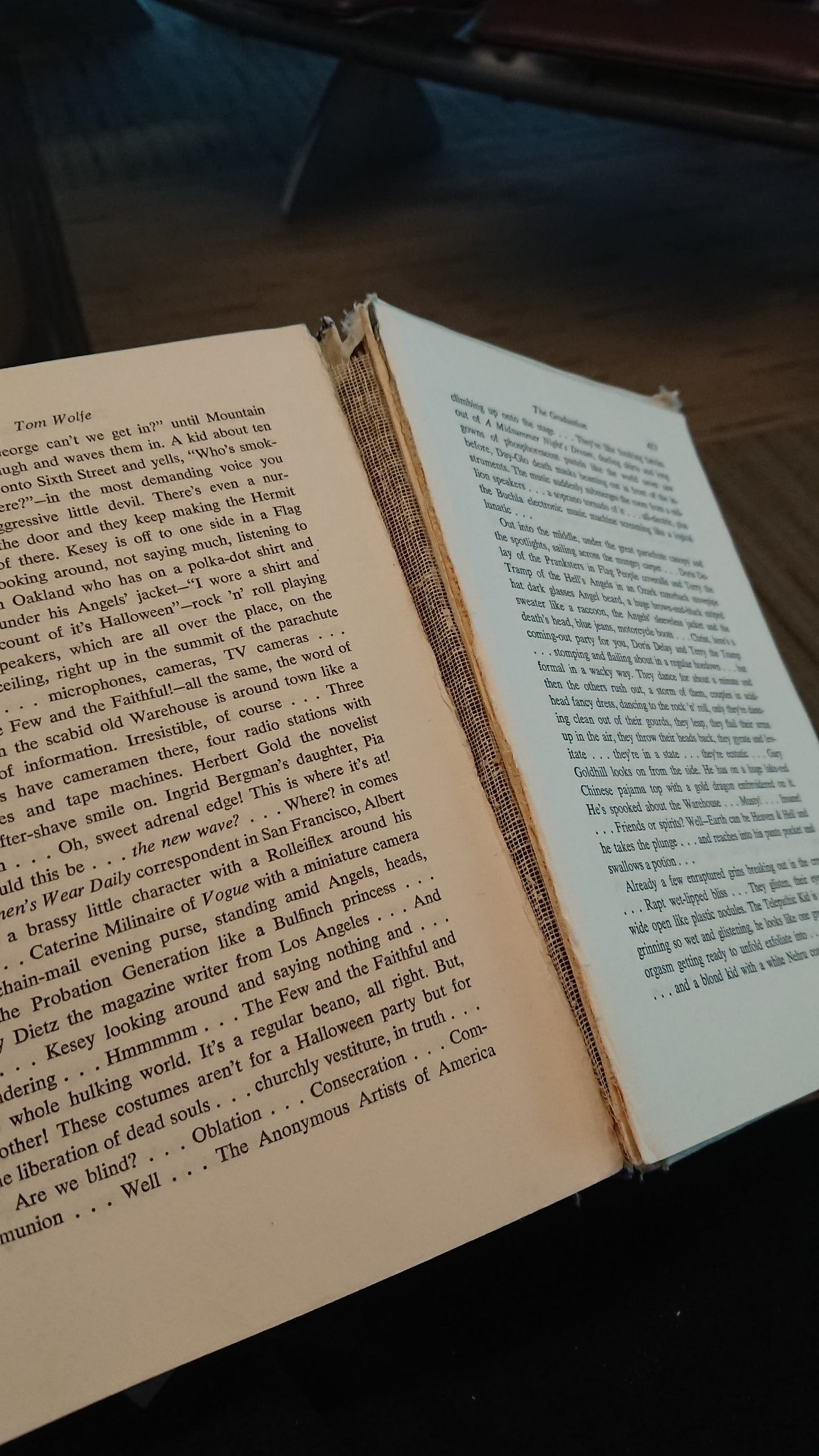

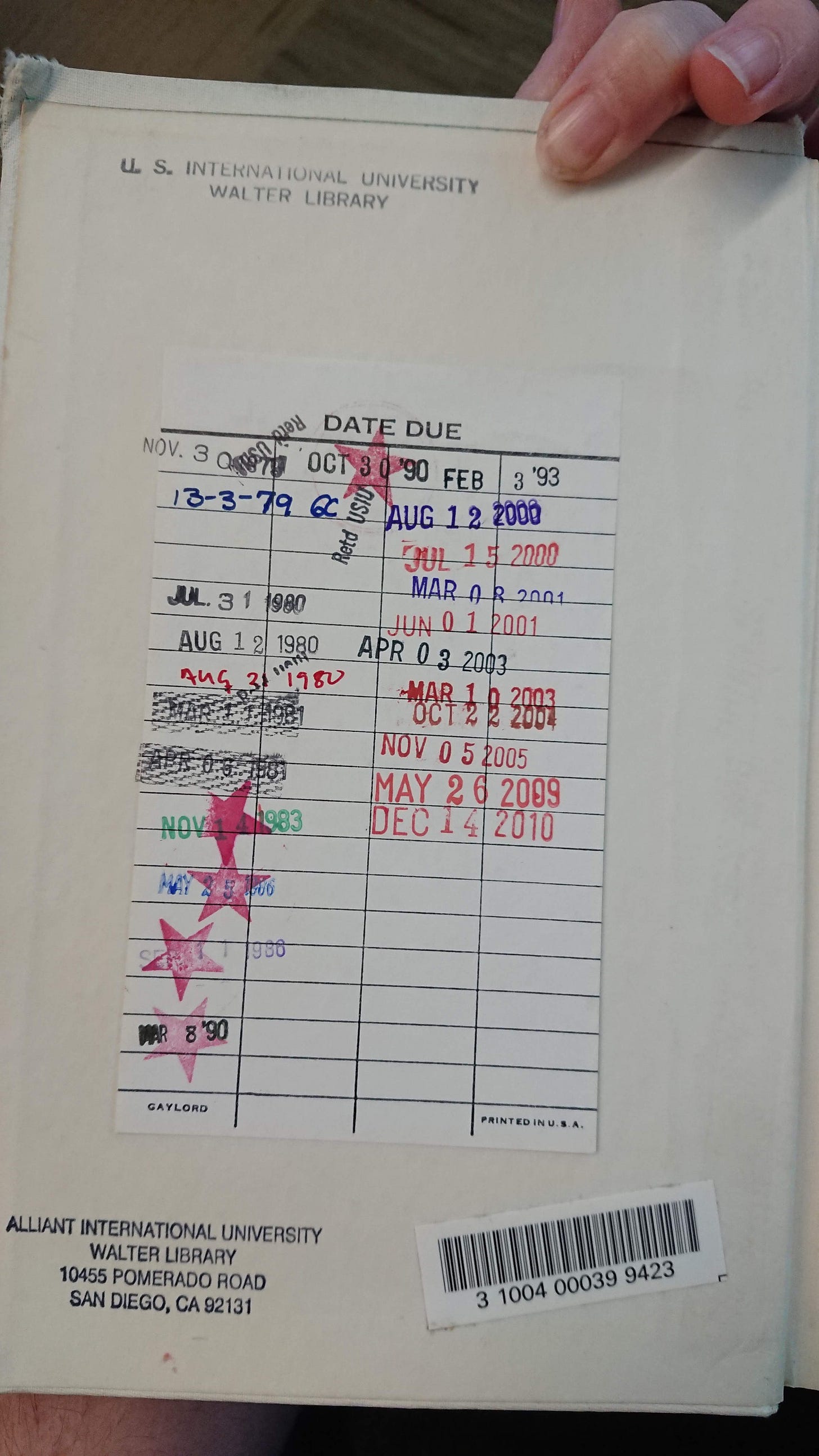

I made sure to request a first edition of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test when I got it through Link+; I wanted to encounter it in the same exact form it had originally come into the world. When my hold came in, I picked up a white hardback from the library that was in pretty good condition even after 50 years of circulation, although I really wanted to mend the split textblock. The artifact and its circulation history was more impressive to me than the text at that point.

Reading it was a schlep, not least of all because by that point I was commuting from San Francisco to Santa Clara daily for work (driving I might add—no luxurious time reading on a train or a bus for me, unless I wanted to increase my commute time by 2.5 hours every day) and—surprise surprise—I didn’t finish it in time for discussion group (a move I often pulled on the ladies of the book club I ran at USF).

Wolfe really soured my views of the Merry Pranksters. Being on the bus sounded hot and uncomfortable, and it didn’t even seem like they were on acid very much. I found myself judging their incompetence, shuddering at the prospect of ever thinking it would be cool to go on a trip like that with a group of burnouts like that, and feeling like a square—like Dylan said, Never trust anyone over 30. The fact they had expensive camera equipment and were trying to make a movie out of their insane voyage across the country to the 1964 World’s Fair in New York passed over me like an absurd detail. None of the characters seemed real; they just seemed like empty hanger-ons to the expiring Ken Kesey fame machine.

The book as artifact was good, Wolfe’s writing was difficult to get in the groove for, and the best part was the book group discussion at the library. It was September, warm and sunny like it gets in San Francisco that time of year. We had the windows open to the little courtyard outside the rec room downstairs where we met. One woman, who came all the way from Oakland for the discussion group sometimes, said she had met Allen Ginsburg and when I remarked that was cool, she tore him to shreds, calling him a self-absorbed ego maniac prick. Alas, our heros fall once we know them.

Towards the end of the meeting, the organizer/moderator led up to a long comment by saying, “I assume none of us here know what taking LSD feels like from from our own experience.” A pause ran through the conversation as several of us exchanged glances. The woman from Oakland piped up, “I certainly have taken acid.” Turns out the majority of us could call on firsthand experience during the portion of the meeting when we were finally allowed to bring personal experience into the discussion. Book discussion at the public library turned into a bunch of old hippies talking about their acid trips.

To give moving life and color to the Merry Pranksters is to understand them as the West coast prototype for the hippie. To see their technicolor bus converted into a camper pulled over by the Highway Patrol in 1964 Arizona is to wonder, Hmm, Americans couldn’t despise them yet, because Americans couldn’t comprehend them yet. To see the moving image in unfaded, true color and quality 16 mm film impresses the truth: this really did happen, and Americans could halfway buy the Merry Prankster’s cover: they were making a movie. American as Hollywood, American as explorers into an altered consciousness.

It is possible to see this in moving image because a 2011 documentary called Magic Trip pieces together the actual footage Ken Kesey never released publicly. Yet, the footage is housed at the UCLA Television and Film Archive, accessible to anyone with a legitimate research need.

The hippie as a cultural phenomena busted into the media about three years after the Merry Pranksters did their voyage across the U.S from Ken Kesey’s home in La Honda, California to New York and back—they were too young to be beatniks, too old to be hippies, but had Neal Cassady—Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty—at the wheel, so high on speed and deep in verbal psychosis that he never stopped talking nonsense—a truth that occurs to me now as sad and freaky after I idolized On the Road in High School. Then the Merry Pranksters collided with Kerouac in New York and he was an alcoholic tool by that time—an old guy. I remember the way he went downhill in Florida at the end of his life. A wave of repulsed pity passes over me thinking of it.

But for the smiley Merry Pranksters bum rushing Leary, Ram Dass, and their uppity East coast LSD community in upstate New York, they pretended to let the rejection slide off their backs, choosing a nearby waterfall as a set for the next scene in their movie. The laid back West coast acid heads win this round of the cool contest.

In their technicolor and motion picture, in their sensuous bodies given flesh, this handful of opt-outs become pretty actors in love and hate with their companions; they frolic in green fields with flowers in their hair. And I thank the people who did the archival research, and who painstakingly edited the narrative together, who gave body and life to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.

Where were you in your life when you read The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test? Leave a comment below!

Header image: By Rcarlberg - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40152572